ENG 231 GROUP WORK:

NATIVE AMERICAN ORAL NARRATIVES

1. What according to the Pima and the Iroquois existed at the beginning of time?

2. In the Iroquois creation story the monsters are concerned when Sky Woman sinks into the dark world. What does their reaction tell us about the nature of monsters and the lower world?

3. Is the Iroquois creation myth still an Iroquois text if it has been translated into English? Does such a translation so alter the meaning that it is no longer accurate to speak of it as Iroquoian, or should the fact of translation merely make readers more cautious, less eager to assume that they understand it? Is it better for non-Indians to have no access to such texts than to have texts that may be contaminated or inaccurate?

4. The theme of rival twins is widespread in the Americas and in the Bible. What cultural anxieties or issues does this theme address? What might account for its popularity?

BRADFORD AND MORTON

1. What strategies does Morton use to satirize the Puritans in New English Canaan? How do the names he gives to the various characters in his tale undermine Puritan values and structures of authority? What is the significance of the title of his book?

2. Context: How does Morton's prose compare to Bradford's "plain style"? Bradford draws most of his metaphors and allusions from the Bible; what sources does Morton draw upon? What kind of identity is Morton trying to construct for himself through his literary style?

Context: How does Morton's prose compare to Bradford's "plain style"? Bradford draws most of his metaphors and allusions from the Bible; what sources does Morton draw upon? What kind of identity is Morton trying to construct for himself through his literary style?

3. Exploration: Morton's portrait of Native Americans is quite different from the accounts offered by most other seventeenth-century American writers. What qualities does he ascribe to the Indians? How does his description of Native American culture compare to his description of Puritan culture? What reasons might Morton have had to portray the Indians so positively? Why do you think Morton's relationship to Native Americans was so threatening to the Puritans at Plymouth Plantation?

Exploration: Morton's portrait of Native Americans is quite different from the accounts offered by most other seventeenth-century American writers. What qualities does he ascribe to the Indians? How does his description of Native American culture compare to his description of Puritan culture? What reasons might Morton have had to portray the Indians so positively? Why do you think Morton's relationship to Native Americans was so threatening to the Puritans at Plymouth Plantation?

4. Exploration: What genre do you think New English Canaan falls into? Is it a history, a satire, a travel narrative, a promotional brochure, or some combination thereof?

Exploration: What genre do you think New English Canaan falls into? Is it a history, a satire, a travel narrative, a promotional brochure, or some combination thereof?

JOHN WINTHROP

1. Locate typologizing moments in Winthrop's "Model of Christian Charity" (The sermon is a particularly good source since Winthrop notes many parallels between the Puritans and the Old Testament Hebrews within it.) Consider the significance of the Puritans' insistence on understanding their own history as prefigured by the Bible. What kinds of pressures might this tendency to read biblical and divine significance into everyday affairs put on individuals and on communities? How might it work to comfort and reassure people?

Locate typologizing moments in Winthrop's "Model of Christian Charity" (The sermon is a particularly good source since Winthrop notes many parallels between the Puritans and the Old Testament Hebrews within it.) Consider the significance of the Puritans' insistence on understanding their own history as prefigured by the Bible. What kinds of pressures might this tendency to read biblical and divine significance into everyday affairs put on individuals and on communities? How might it work to comfort and reassure people?

2. Why has Winthrop's metaphor of the "City on a Hill" had so much influence on American culture? Do you see evidence of the endurance of this idea within contemporary public discourse?

Why has Winthrop's metaphor of the "City on a Hill" had so much influence on American culture? Do you see evidence of the endurance of this idea within contemporary public discourse?

ANNE BRADSTREET AND EDWARD TAYLOR

1. What are some of the recurring themes and images in Bradstreet's poetry? How does she balance abstract, theological concerns with personal, material issues? What does Bradstreet's poetry tell us about motherhood and marriage in Puritan New England?

What are some of the recurring themes and images in Bradstreet's poetry? How does she balance abstract, theological concerns with personal, material issues? What does Bradstreet's poetry tell us about motherhood and marriage in Puritan New England?

2. In the poem "Here Follows Some Verses upon the Burning of Our House," how does Bradstreet struggle with her Puritan commitment to the doctrine of "weaned affections" (the idea that individuals must wean themselves from earthly, material concerns and focus only on spiritual matters)? How does she turn the experience of losing her possessions to spiritual use? Does she seem entirely resigned to casting away her "pelf" and "store"? In what terms does she describe the "house on high" that God has prepared for her?

In the poem "Here Follows Some Verses upon the Burning of Our House," how does Bradstreet struggle with her Puritan commitment to the doctrine of "weaned affections" (the idea that individuals must wean themselves from earthly, material concerns and focus only on spiritual matters)? How does she turn the experience of losing her possessions to spiritual use? Does she seem entirely resigned to casting away her "pelf" and "store"? In what terms does she describe the "house on high" that God has prepared for her?

Comprehension: How does the main text of "Meditation 8" relate to the poem's prefatory biblical citation ("John 6.51. I am the Living Bread")? What is the extended metaphor at work in this poem? What is the significance of Taylor's focus on a basic domestic chore that is usually performed by women? Do you notice similar imagery in any of Taylor's other poems?

3. Compare Taylor's "Prologue" to the Preparatory Meditations and "Meditation 22" with Bradstreet's "Prologue" and "The Author to Her Book." How do these Puritan poets deal with their anxiety about their own literary authority? Do they share similar concerns? How are they different? What conclusions do they arrive at?

4. The only book of poetry known to have had a place in Taylor's personal library was Anne Bradstreet's Tenth Muse. Does his poetry seem influenced by her work? How is it different? How does his work fit or not fit within the tradition of "plain style

The only book of poetry known to have had a place in Taylor's personal library was Anne Bradstreet's Tenth Muse. Does his poetry seem influenced by her work? How is it different? How does his work fit or not fit within the tradition of "plain style

MARY ROWLANDSON

1. The subject of food receives a great deal of attention in Rowlandson's Narrative. How does Rowlandson's attitude toward food change over the course of her captivity? Why is she so concerned with recording the specifics of what she ate, how she acquired it, and how she prepared it? What kinds of conflicts arise over food? What do her descriptions of eating tell us about Native American culture and about Rowlandson's ability to acculturate?

2. How does Rowlandson use typology within her Narrative? What kinds of biblical images does she rely on to make sense of her captivity? How does her use of typology compare with that of other writers in this unit (Winthrop or Taylor, for example)?

3. In his preface to the first edition of Rowlandson's Narrative, published in 1682, Increase Mather describes her story as "a dispensation of publick note and of Universal concernment" and urges all Puritans to "view" and "ponder" the lessons it holds for them. Does Rowlandson always seem to understand her captivity in Mather's terms? How do the moments when Rowlandson narrates her experience as personal and individual complicate this imperative to function as a "public," representative lesson for the entire community?

4. Many scholars view the captivity narrative as the first American genre and trace its influence in the development of other forms of American autobiographical and fictional writings. Why do you think the captivity narrative became so popular and influential? What might make it seem particularly "American"? Can you think of any nineteenth- or twentieth-century novels or films that draw on the conventions of the captivity narrative?

5. Rowlandson opens her Narrative with totalizing, dehumanizing descriptions of Native Americans as "hell-hounds," "ravenous beasts," and "barbarous creatures." As the text progresses, however, she seems to become more willing to see her captors as individuals, and even as people capable of humanity and charity. analyze her portraits of individual Indians and trace the evolution of her attitude toward Indians in general. Which Native Americans come in for the most criticism? Which does she view more positively? What might motivate her varying assessments? How might changes in Rowlandson's own status within the Wampanoag encampment influence her attitude toward individual Indians?

John Woolman and Samson Occom

1. Woolman's Journal has been celebrated as a particularly beautiful and effective example of "plain style." How does his use of this style compare to that of other plain stylists discussed in this unit (Bradford, Bradstreet, and Penn, for example)? What kinds of values and beliefs might Woolman's style reflect? Are they the same or different from the values held by Puritan plain stylists?

2. How do Woolman's concerns prefigure later social movements in America (abolitionism, civil rights issues, the development of welfare programs, for example)? Can you trace his influence in any contemporary discussions of social justice issues? What might Woolman think of contemporary American society? How would he feel about the ongoing problems of racism, bigotry, pov-erty, violence, and materialism?

3. When does Occom feel that he is being treated unfairly? What is his concept of justice? How does he deal with the prejudice and mistreatment he experiences? What rhetorical strategies does he use to present his complaints in his narrative?

4. Compare Occom's description of Indian life and Indian identity with the perspectives on Indians offered by other writers in this unit (Bradford, Morton, or Rowlandson, for example). How does Occom's narrative of Native American life complicate or challenge the perspectives of the English writers? Does his account of Indian culture have anything in common with their accounts?

BENJAMIN FRANKLING AND JONATHAN EDWARDS

1. To what does Franklin attribute his success? What kind of advice does he offer to readers who want to model their life on his?

2. Benjamin Franklin and Jonathan Edwards were born within three years of each other, but, despite their similar ages, the two men had radically different perspectives and beliefs. Compare Franklin's Autobiography with Edwards's "Personal Narrative." How are these writers' views on morality, personal responsibility, human nature, and/or the limits of human knowledge similar? How are they different? How does Franklin both draw from and reject the Puritan tradition that was so important to Edwards?

3. What language does Edwards use to describe his experience of grace in his "Personal Narrative"? What kinds of difficulties does he seem to have articulating his experience? What imagery and metaphors does he employ?

4. What was the Great Awakening?

5. Edwards was profoundly affected by the beauty of the natural world and understood it to be an expression of God's glory. How does Edwards use natural imagery in his sermons?

6. During the Great Awakening preachers and clerics had a tremendous influence on American culture: they captivated audiences with their powerful messages and transformed people's beliefs and the way they lived their everyday lives. What charismatic figures seem to exert this kind of influence over American culture today?

Thomas Jefferson

1. What grievances against British rule are outlined in the Declaration of Independence?

2. Read the contextual material in "The Awful Truth: The Aesthetic of the Sublime" featured in class notes. Examine Jefferson's description of the Natural Bridge in Query V of Notes on the State of Virginia. How does Jefferson describe the Natural Bridge? What effect does it have on him when he visits it? Why does he shift to the second person when he describes the Bridge's effects? Why does he view it as "the most sublime of Nature's works"? How does the Bridge compare to other natural or human-made wonders you may have visited (the Grand Canyon, the Rocky Mountains, the Empire State Building, the Hoover Dam, or Niagara Falls, for example)?

3. The Puritans' Mayflower Compact, John Winthrop's "Model of Christian Charity," and the Declaration of Independence all function as early American articulations of shared values. How do these documents compare to one another? How did American values change over the course of 150 years? What does the Declaration, an eighteenth-century text, have in common with the Puritan documents?

4. Sentences and phrases from the Declaration of Independence are often recycled in American political and cultural documents. Think of some instances when you may have heard the Declaration quoted. Which sections are quoted most often? Why? How do you think interpretations and uses of the language of the Declaration have changed since Jefferson's time?

Phyllis Wheatley

1. In "To His Excellency General Washington," Wheatley refers to America as "Columbia"--a feminized personification of the "land Columbus found." While this designation of America as "Columbia" became commonplace in the years following the Revolution, Wheatley's use of the term marks its first-known appearance in print. Why might Wheatley have been interested in coining this description of America? How does she describe "Columbia" in her poem? What does the ideal of "Columbia" seem to signify for her? How does Wheatley's depiction of America as "Columbia" compare to other textual and visual representations of "Columbia"?

2. In his efforts to support his arguments for the racial inferiority of black people in Notes on the State of Virginia, Thomas Jefferson famously dismissed the artistic merit of Wheatley's poetry: "Religion indeed has produced a Phyllis Whately [sic]; but it could not produce a poet. The compositions published under her name are below the dignity of criticism." Why do you think Jefferson felt compelled to denounce Wheatley in this way? What is at stake in his refusal to "dignify" her poetry with his criticism?

3. Literary and cultural critic Henry Louis Gates Jr. has argued that Phillis Wheatley's poetry is enormously significant in that it "launched two traditions at once--the black American literary tradition and the black woman's literary tradition." How did Wheatley's poetry influence subsequent African American poets and writers, such as nineteenth-century writers of slave narratives or the poets of the Harlem Renaissance? How does her work deal with issues of gender? How do we reconcile Gates's claims for her status as a founder with the fact that Wheatley's work was largely forgotten after her death until abolitionists republished some of her poems in the mid-nineteenth century?

HECTOR ST. JOHN de CREVECOUER

1. Many assume that James, the narrator of Letters from an American Farmer, corresponds to Crèvecoeur himself and the work is an essentially autobiographical one. However, James is an invented persona and at time Crevecoeur uses the distance between himself and his narrator to produce ironic effects (the horrific description of James's encounter with the tortured slave in Letter IX is used to make a point). How does the narrator react to the spectacle of the dying slave in the cage? Why doesn't he take any action to help the man? What are we to make of the line informing us that the narrator "mustered strength enough to walk away"? How does he interact with the owners of the slave when he eats dinner with them later that evening?

2. Letters from an American Farmer does not fall easily into a particular genre; it has been read as a travel narrative, an epistolary novel, an autobiography, a work of natural history, and a satire. To explore this question of genre and audience, imagine that you are Crèvecoeur's publisher and are responsible for marketing his book to eighteenth-century readers. How would you describe and promote the book, and what readers would you hope to reach? Would the book be more interesting to Europeans or to Americans? How would they summarize the book for marketing purposes? Where would you shelve the book in a bookstore?

3. What kinds of problems does Crèvecoeur's narrator face in Letter XII, "Distresses of a Frontier Man"? How does this letter compare to the narrator's earlier descriptions of his life in America? What has caused the change in his tone?

4. What answers does Crèvecoeur offer to the question he poses in the title of Letter III, "What Is an American"? What economic, social, religious, and racial qualities characterize an American in Crèvecoeur's view? How does his description of the American character compare to those offered by other authors in Unit 4 (Tyler, Franklin, or Emerson, for example)?

5. How does Crèvecoeur describe Native Americans in Letters from an American Farmer? How do they fit into his ideas about who should be considered a true American? Why does his narrator contemplate living among the Indians in Letter XII? How does Crèvecoeur's description of Native American life compare to William Apess's account?

6. For a text written before the nineteenth-century abolitionist movement, Letter IX contains an unusually graphic description of the shocking and terrifying abuses committed under the slave system. Why does Crèvecoeur include this description? What are readers supposed to make of his narrator's rather apathetic response to the horrible scene he encounters? How does Crèvecoeur's portrait of slavery compare to later, nineteenth-century accounts of slave abuse (texts by Frederick Douglass, Harriet Jacobs, or Harriet Beecher Stowe might make good comparisons)?

Appess

1. Examine Apess's use of scripture in "An Indian's Looking-Glass." Notice that he does not employ biblical quotations in the first half of his essay. Why does Apess use the Bible when he does? How does he use scripture to back up his arguments? What kinds of passages does he choose?

2. In "An Indian's Looking-Glass for the White Man" Apess claims that the Indians of New England are "the most mean, abject, miserable race of beings in the world." Why, according to Apess, has Native American society reached such a low point? What reasons does he give for the Indians' abjection?

3. In the opening paragraphs of his "Eulogy on King Philip," Apess twice compares Metacomet to George Washington. Why do you think Apess would have been interested in likening his Native American ancestor to Washington? How does he compare the respective "American Revolutions" led by each man? What associations and sentiments might Apess have been trying to generate in his Boston audience?

4. How does Apess's use of Christian values and biblical quotations in "An Indian's Looking-Glass" compare to Phillis Wheatley's use of Christian imagery and language in her poetry?

5. Samson Occom, Apess trained as a minister and adopted white Christian values only to become frustrated by the disparity between Christian teachings and the harsh realities of white treatment of Native Americans. How does Apess's "An Indian's Looking-Glass" compare to Samson Occom's "A Short Narrative of My Life"? What experiences do they have in common? Do they use similar strategies to protest unfair treatment of Native Americans? How are their protests different? How do they characterize white prejudice?

EMERSON

1. One of the earliest reviews of Nature pronounced the book incomprehensible: "the effort of perusal is often painful, the thoughts excited are frequently bewildering, and the results to which they lead us, uncertain and obscure. The reader feels as in a disturbed dream." Read the "Introduction" to Nature, paying particular attention to Emerson's formulation of nature as the "Not Me." By dividing the universe into nature and the soul, Emerson was not claiming that these two essences have nothing to do with one another; rather, his point was that each particle of the universe is a microcosm of the whole. Discuss the concept of the microcosm. The key to Emerson's philosophy in Nature lies in his fundamental belief that everything in nature and in the soul is united in correspondence, that a universal divinity has traced its likeness on every object in nature, on every soul, and thus on every human production.

2. According to Emerson, what is "nature"?

3. Emerson opens Chapter 1 of Nature by pointing out that the stars afford humans insight into "the perpetual presence of the sublime." Review the explanation of the "sublime" featured in the context "The Awful Truth: The Aesthetic of the Sublime," and think about Emerson's relationship to this aesthetic movement. Why does Emerson open his book by invoking the idea of "sublimity"? What effect does he believe visions of sublime natural beauty have on viewers?

4. What relationship does Transcendentalism have to traditional religious beliefs? Would you characterize Transcendentalism as a secular movement? Does it have anything in common with New England Puritanism? With Quaker doctrine? With Deism?

In order to make connections and understand the important theological differences between various early American religious movements, make a chart of these traditions, filling it out as a class

THOREAU

Discussion Questions: "Resistance to Civil Government"

1. What role does the "state" play in your life? Do you have a contract or an "implied contract with the state? Consider "state" in its broadest sense: country, religion, business, school.

What role does the "state" play in your life? Do you have a contract or an "implied contract with the state? Consider "state" in its broadest sense: country, religion, business, school.

2. Select any passage from "Resistance to Civil Government" that especially provokes, stuns, annoys, amuses, or confuses you. Discuss why you choose the passage.

Select any passage from "Resistance to Civil Government" that especially provokes, stuns, annoys, amuses, or confuses you. Discuss why you choose the passage.

3. What do you owe the state? When you do have the right or even the obligation to rebel against the state? What does Thoreau say about this?

What do you owe the state? When you do have the right or even the obligation to rebel against the state? What does Thoreau say about this?

4. What is more important? The state or the individual? What happens when we rephrase the question: "What is more important? Autonomy or interdependency? Community or society? Is any person above the law? Socrates asked, "Ought a man to do what he admits to be right, or ought he to betray the right? Is the concept of civil disobedience above the law?

What is more important? The state or the individual? What happens when we rephrase the question: "What is more important? Autonomy or interdependency? Community or society? Is any person above the law? Socrates asked, "Ought a man to do what he admits to be right, or ought he to betray the right? Is the concept of civil disobedience above the law?

5. What is the difference between disobedience and dissent and civil disobedience?

What is the difference between disobedience and dissent and civil disobedience?

6. Does the United States have a tradition of civil disobedience? Indeed, does "rebellion" define our character?

Does the United States have a tradition of civil disobedience? Indeed, does "rebellion" define our character?

7. How is civil disobedience an assault on the democratic society, an affront to our legal order, and even an attack on our Constitutional government? How do you respond to Antigone's criticism of Creon: "I did not think your orders were so strong that you, a mortal man, could overrun the gods' unwritten and unfailing laws."

How is civil disobedience an assault on the democratic society, an affront to our legal order, and even an attack on our Constitutional government? How do you respond to Antigone's criticism of Creon: "I did not think your orders were so strong that you, a mortal man, could overrun the gods' unwritten and unfailing laws."

8. Cite some contemporary issues that illustrate this apparent conflict between the state and the individual. Be prepared to discuss you position on each issue.

Cite some contemporary issues that illustrate this apparent conflict between the state and the individual. Be prepared to discuss you position on each issue.

• Should smoking be banned from public restaurants?

Should smoking be banned from public restaurants?

• Should school funds be used to finance "fringe" student groups?

Should school funds be used to finance "fringe" student groups?

• Should federal funds be used to finance art foundations or even National Public Radio?

Should federal funds be used to finance art foundations or even National Public Radio?

• Abortion

Abortion

JAMES FENIMORE COOPER

1. Because it was set in England and featured only English characters, Cooper's first novel, Precaution (which he published anonymously), was assumed to be the work of a British citizen. Reviewers also concluded that the author was a woman because the novel centered on domestic scenes and social manners. Perhaps distressed by this misreading of his nationality and gender, Cooper focused many of his subsequent novels on American subjects and masculine heroes. What strategies does Cooper use to identify his work as both "manly" and "American." What does Cooper see as appropriate behavior for a man and for an American? Which characters represent his ideals of American masculinity? How might his books respond to the notion, current in nineteenth-century America, that novel reading was a frivolous and feminine pursuit?

2. Settings in works of fiction are often invented to symbolize or encapsulate the conflicts that will be developed in the story. How does Cooper describe the frontier community of Templeton in The Pioneers? How does the town function as a contact point between "civilization" and the wilderness? What kinds of hardships do the townspeople face? What is their vision of "progress"?

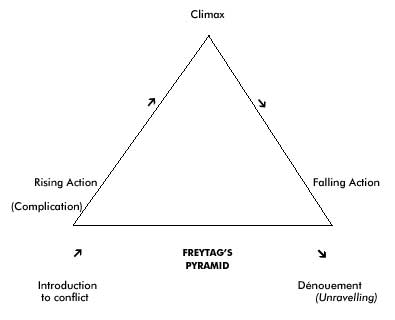

3. In 1863, German critic Gustav Freytag argued that the typical plot of a five-act play had a pyramidal shape. This pyramid consists of five stages: an introduction to the conflict, rising action (complication), climax, falling action, and a dénouement (unraveling). Although this pattern, known today as Freytag's pyramid, originally referred to drama, critics have applied the concept to fiction as well. How might we use Freytag's pyramid to analyze the plot development of The Pioneers? In what stage of the pyramid would the chapters "The Judge's History of the Settlement" and "The Slaughter of the Pigeons" fall? What is the nature of the conflict between Judge Temple and Natty Bumppo? How are their values opposed?

4. In both "The Judge's History of the Settlement" and "The Slaughter of the Pigeons," Cooper describes the way "settlement" and "civilization" exploit and disrupt the natural abundance of the wilderness. While the Judge tends to view this process as "improvement," Natty condemns it as destructive and wasteful. What is Cooper's position, on the environmental impact of European-American settlement? In what respects does he seem to side with the Judge's position, and in what respects does he seem to side with Natty? How does The Pioneers raise environmental issues that still concern us today? How do contemporary debates about issues such as logging old-growth forests, salmon fishing, and drilling for oil in the Alaskan National Wildlife Refuge grow out of some of the same controversies raised in The Pioneers?

5. Natty Bumppo has been described as the "first American hero" in U.S. national literature. What qualities make Natty heroic? How does he deal with the tensions between "wilderness" and "civilization" that structure life in and around Templeton? How does he deal with his existence on the border between Native American and Euro-American culture? How did Cooper's creation of Natty influence American literature? What subsequent literary heroes share some of Natty's qualities?

CAROLINE STANSBURY KIRKLAND

1. How do men and women experience frontier life differently, according to Kirkland's analysis in A New Home? What distinct problems and anxieties do women encounter in their new homes in the West?

2. A New Home--Who'll Follow? sold well and received favorable notices from important reviewers such as William Cullen Bryant and Edgar Allan Poe. Yet Kirkland's book marks a distinct shift from previous popular descriptions of frontier life--it is neither romanticized nor sentimental nor filled with tales of masculine heroism and adventure. Why do you think Kirkland's work appealed to nineteenth-century readers? Do you think she appealed to the same kind of audience that read Cooper and Nat Love?

3. Kirkland describes in detail many of the domestic commodities that circulate within her frontier community, both to complain about her ungrateful neighbors' habit of borrowing her possessions and to poke fun at pioneer women's pretensions in owning such luxuries as "silver tea-pots" and fancy dresses. What is the role of commodities in Kirkland's narrative? How does she feel when she is accused of "introducing luxury" into the community when she displays her parlor carpet? How do commodities function to distinguish one "class" of women from another within the village? What kind of symbolic importance do the women in Pinckney attach to their furniture and household goods? How does gender structure the people of Pinckney's attitudes toward domestic objects, both decorative and useful?

4. Realism is usually thought of as a post-Civil War development in American literature, probably because male writers did not adopt it until the 1860s and 1870s. Kirkland's work provides clear evidence of an earlier incarnation of realism, yet she has never received the kind of critical attention afforded to the male writers who are seen as realism's "pioneers"--writers like Mark Twain and William Dean Howells. Ask students to think about the assumptions that inform our categorization and canonization of particular American writers. How does gender impact writers' reputations? How do we decide what constitutes a "school" or "movement" within American literature?

NAT LOVE

1. During both his career as a cowboy and his stint as a railroad worker, Love records his feelings of awe for the natural beauty and vast expanses of the United States. Think about his relationship to the western landscape and to America as a nation. At the close of Chapter XX, after detailing the beauties of the land, Love exhorts his reader to "let your chest swell with pride that you are an American." He goes on to proclaim, "I have seen a large part of America, and am still seeing it... America, I love thee, Sweet land of Liberty, home of the brave and the free." How does the landscape contribute to Love's sense of pride in his country? How does Love's status as a former slave complicate his celebration of the "liberty" and "freedom" of the United States?

Grand Canyon from Below Grandview Point

Yellow Stone National Park

2. When Love is taken captive by the Native Americans he calls "Yellow Dog's Tribe," he attributes their generosity in sparing his life both to his own bravery and to the fact that he is black, since, as he puts it, the tribe "was composed largely of half breeds, and there was a large percentage of colored blood in the tribe." Despite this acknowledgment of shared racial heritage, Love conspicuously distances himself from the Native Americans who adopt him. Ask students to consider the racial politics of this scene. How does Love respond to his captivity? How does he portray his Native American/African American captors? What seems to be his role within the tribe's social hierarchy and how might it be influenced by race? How and why does he escape?

3. Readers might expect Love to be somewhat bitter about the development of the railroad since it led to the demise of his cowboy lifestyle, yet he embraces his career as a Pullman Porter. What does Love find appealing about the railroad? Does his attitude reflect a typically American attitude toward technological change? What insights do his discussions of rail line procedure give us into the corporate structure and philosophy of the Pullman Company in the nineteenth century? What is Love's attitude toward the management of the railroad?

4. Why do you think pop cultural representations of the "Old West" usually portray both cowboys and pioneers as Anglo-Americans? How does Nat Love's autobiography challenge traditional images of cowboy life? Does Love's narrative also participate in certain stereotypes?

WALT WHITMAN

1. Although you may have picked up on the homoerotic imagery of many of Whitman's poems, keep in mind that male-male eroticism was not so clear to nineteenth-century readers, who were far more scandalized by his explicit descriptions of heterosexual sex. The term "homosexual" did not exist in 1860, so Whitman's poems were struggling to construct a new sexual identity and create a new language for erotic love between men. Analyze stanzas VII and VIII of Live Oak, with Moss and/or the "Twenty-eight Bathers" section in Song of Myself in this context. Why does Whitman adopt a feminine persona in his narration of the "Twenty-eight Bathers"? How does Whitman struggle with his commitment to being a "public," national poet and his desire to record his private erotic feelings in Live Oak, with Moss? How does he describe his love for men, given that a vocabulary for homosexuality was unavailable to him?

2. Although the early editions of Leaves of Grass contain many eloquent celebrations of the vastness and grandeur of the American continent, Whitman had actually done very little traveling when he wrote them (his trip to New Orleans was his only significant travel experience until late in life). Think about why cities and landscapes Whitman could only imagine affected him so deeply. To what kinds of cultural myths and ideals was he responding? How might Whitman's lyrical descriptions of America's geographic expanse and demographic diversity have impacted his readers' ideas about the landscape and the nation?

3. In Song of Myself, Whitman attempts to reconcile and bring into harmony all the diverse people, ideas, and values that make up the American nation. Which groups of people does he choose to focus on particularly? How does he describe people of different races, social classes, genders, ages, and professions?

NATHANIEL HAWTHORNE

1. Notice how the rational and objective pursuit of scientific truth blurs into the obsessive and personal pursuit of individual desire in "Rappaccini's Daughter" (this is true in different ways for all three of the male characters, Giovanni, Rappaccini, and Baglioni). Why might Hawthorne deliberately challenge the distinction between science and passion in this story?

2. What are we to make of Rappaccini's final justification to Beatrice of his perverse experiment: "'Wouldst thou, then, have preferred the condition of a weak woman, exposed to all evil, and capable of none?'" Why does it matter that Beatrice is a woman? How would the story be different if Rappaccini had endowed a male child with the venomous powers of the poison plant? How can you relate this story to the nineteenth-century "cult of true womanhood" discussed in the Core Context "The Spirit Is Willing: The Occult and Women in the Nineteenth Century"?

3. What are some current ethical issues of science and "progress." Is Rappaccini a twisted and perverted emblem of the scientific method or does he stand for a general ethical failure of science?

CHARLOTTE PERKINS GILMAN

1. Describe the narrator of "The Yellow Wall-paper" as precisely as you can. Why does she spend all of her time in the nursery? What is "wrong" with her? To what extent does she change over the course of the story?

2. Describe the Wall-paper. Why is the narrator both fascinated and repulsed by it?

3. By the end of the story, the narrator seems to believe she has achieved a victory: " 'I've got out at last,' said I, 'in spite of you and Jane! And I've pulled off most of the paper, so you can't put me back!' " Do you agree that she has emerged victorious? If so, in what sense?

4. How does the narrator's husband, John, treat her? She notes, "He says that with my imaginative power and habit of story-making, a nervous weakness like mine is sure to lead to all manner of excited fancies, and that I ought to use my will and good sense to check the tendency." Why does he emphasize her "imaginative power," and to what extent do you think Gilman wants us to agree with John's opinion?

EDGAR ALLEN POE

1. Does "Ligeia" represent supernatural events? What difference does your answer make to our understanding of the story?

2. How does the setting of "Ligeia" affect your understanding of the story?

3. In an essay about composing literature, Poe wrote the following: "the death, then, of a beautiful woman is, unquestionably, the most poetical topic in the world--and equally is it beyond doubt that the lips best suited for such topic are those of a bereaved lover." What do you think he meant by this? How does "Ligeia" fit into this philosophy of literature? Consider how the narrator describes Ligeia, how he feels and what he thinks about her: what does the story suggest about the proper roles or characteristics of men and women? How is Ligeia like and unlike the ideal woman as conceived by adherents of the cult of true womanhood?

4. The narrator is unsure about many things in "Ligeia," including when and where he met Ligeia, her last name, and whether he is mad. In fact, it is possible to say that the story is about uncertainty: "Not the more could I define that sentiment, or analyze, or even steadily view it," says the narrator at one point. How does Poe explore the dilemma of ambiguity in "Ligeia"? What does he seem to be saying about the mind's attempt to establish certainty?

ambiguity - Doubtfulness or uncertainness of interpretation. Much gothic literature is considered ambiguous insofar as it rarely presents a clear moral or message; it seems intended to be open to multiple meanings.

EMILY DICKINSON

1. Discuss Dickinson's focus on the "slant" (indirection and ambiguity). What part does the use of the dash play in creating this effect? How does her work differ from Whitman? How does the persona these two poets create for themselves differ?

2. Unlike many of her contemporaries, Dickinson does not write poems with clear moral or ethical messages. Are her poems trying to "teach" us anything? What seems to be the purpose of these poems? Do they make you feel (and if so, feel how)? Do they make you think (and if so, think what)?

3. Dickinson's most famous poem, #465, draws on the nine-teenth century's fascination with death-bed scenes in literature. Unusually, however, this scene is described from the point-of-view of the deceased. What exactly does the poem's narrator experience, both sensuously and psychologically? How does the fly affect the narrator's experience of death?

4. What might Dickinson mean when she writes "Tell all the Truth but tell it slant" (#1129)? Why is there a danger that Truth will blind us unless it "dazzle[s] gradually"? Why does the narrator refer to children in supporting this thesis?

5. What, in poem #258, might "internal difference" mean? What are "the Meanings," and why are they contained in internal difference? Why does the natural experience of a certain winter light provoke reflection on internal difference?

BRITON HAMMON

1. How does Hammon view the Native Americans who capture him in Florida? How does he view the Spanish in Cuba? How does he feel about the Catholicism of his Spanish captors? How does captivity compare with servitude in his experience?

2. What role does Christianity play in Hammon's understanding of his experiences? When and how does he invoke God in the course of relating his story?

3. What is the relationship between Hammon's "Narrative" and the narratives of slave escapes that became popular in the nineteenth century (such as those written by Douglass, Craft, or Jacobs, for example)? What historical factors might have caused the tone and subjects of slave narratives to change so dramatically?

4. At several points in his text, Hammon describes his happiness at seeing the English flag, or "English Colours," and identifies himself as an "Englishman." What does being English seem to mean to Hammon? What insights does the "Narrative" provide us into the role of nationalism and national identity within the maritime world along the Atlantic coasts?

5. How does Hammon's "Narrative" compare with the Indian captivity narratives written by Anglo-Americans in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries (Mary Rowlandson's Narrative, for example)? How are Hammon's concerns different? In what ways are his experiences and reactions similar to those of white captives?

ABRAHAM LINCOLN

1. What kind of audience does Lincoln assume will be listening to his speeches? How do you think nineteenth-century audiences might have been different from audiences today?

2. Why do you think Lincoln chose the verse from the New Testament "A house divided upon itself cannot stand" (Luke 11.17) as the basis for his speech? What significance would this image of a threatened home have for nineteenth-century Americans? How might it have resonated with American ideals of domesticity?

3. Interestingly, Lincoln's now celebrated speech was not well received when he first delivered it on the battlefield at Gettysburg in November 1863. Apparently, it seemed too concise and simple to the audience, which preferred Edward Everett's lengthy two-hour sermon. Why do you think the speech was unsuccessful when Lincoln delivered it? Today the "Gettysburg Address" is often viewed as a model of eloquence. Why has it gained in popularity over time?

4. Today Lincoln is something of an American cultural icon--he is the subject of imposing monuments and his face even circulates on our money. What does Lincoln represent to contemporary Americans? Why is he viewed as such an important president? How does Lincoln's position within American cultural mythology compare to what you know about his biography and political choices? What kinds of myths are important to Lincoln's image?

5. The Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C., is based upon one of the most famous architectural monuments in the world, the temple to Athena found on the Acropolis in Athens, Greece. Why would the architects of the Lincoln Memorial want to use the Parthenon as a model? What does this allusion signify about Lincoln and about America? What does it mean that inside we find Lincoln seated rather than the gold and ivory statue of Athena?

6. Read "When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom'd," Walt Whitman's elegy for Lincoln. What does Whitman admire about Lincoln? Do Lincoln's speeches live up to this eulogy?

DOUGLASS

1. Why does Douglass refuse to narrate the details of his escape in his 1845 autobiography? What effect does this gap in information, and the reason Douglass provides for it, have on his narrative?

2. Before Douglass's violent encounter with Covey, he is given a root by his friend, the slave Sandy Jenkins. Sandy claims that the root is a kind of talisman that will protect anyone who carries it. Although Douglass represents himself as skeptical of Sandy's superstitious belief in the root's power, he does at some level validate the effectiveness of the talisman in the course of his narrative. What is the significance of this invocation of African American folk magic at this point in the narrative?

3. How does Douglass describe Sorrow Songs in his Narrative? How do they affect him personally? What does he believe they signify in slave culture? What does he mean when he says that though they seem "unmeaning jargon," they are "full of meaning" for the slaves?

4. Douglass's autobiographical account of the process through which a "slave was made a man" has often been compared to Benjamin Franklin's narrative of his own self-making. What do these autobiographies have in common? How do these two writers' approach to literacy and writing compare? How does Douglass recast Franklin's ideals to fit the condition of an escaped slave?